Invasion of Okinawa Explained: Timeline & Museum Visits

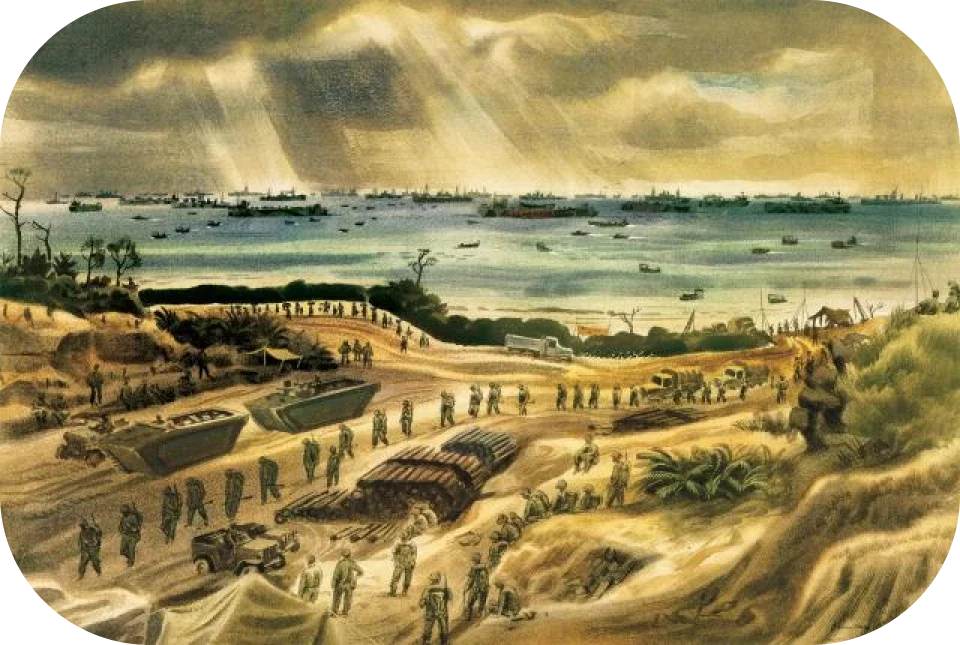

The Battle of Okinawa (April 1–June 22, 1945) – codenamed Operation Iceberg – was the largest amphibious assault of the Pacific War. About 180,000 U.S. troops landed and slogged south through fierce Japanese defenses (the Shuri Line around Shuri Castle), suffering ~12,500 U.S. deaths. Japanese casualties exceeded 110,000, and at least 100,000 Okinawan civilians were killed (some estimates put total casualties ~240,000). The invasion secured Okinawa as a staging base for invading Japan, but at enormous human cost. Today Okinawans observe June 23 as Irei no Hi (“Memorial Day”). Visitors can explore this history at key sites: Okinawa Peace Memorial Park & Museum (Itoman); Himeyuri Peace Museum (Itoman); and the Former Japanese Navy Underground Headquarters (Naha). Each offers exhibits and memorials honoring military and civilian experiences, with English explanations and practical visitor facilities.

Quick Orientation

Okinawa lies at Japan’s southern tip, a strategic springboard in WWII. In Spring 1945, Operation Iceberg brought U.S. Marines and Army divisions ashore to seize airfields and clear the island. The Japanese 32nd Army defended Okinawa with multiple fortified lines, the strongest around the castle-town of Shuri. Familiarize yourself with these terms before diving into the timeline:

- Operation Iceberg: Allied code name for the Okinawa invasion (Apr–Jun 1945). It was a massive combined amphibious and airborne assault – the last major battle of WWII.

- Shuri Line: Japan’s final defensive belt, anchored on Shuri Castle in central Okinawa. American forces fought hilltop-by-hilltop against dug-in positions here.

- Gama: The Okinawan word for limestone caves. During the battle, many civilians and soldiers hid in these caves for shelter. (For example, Shimuku Gama sheltered ~1,000 villagers on L-Day.)

- Irei no Hi: “Memorial Day” observed on June 23. It marks the 1945 end of fighting with island-wide ceremonies and a moment of silence at noon.

- Kamikaze: Japanese suicide pilots (meaning “divine wind”). Okinawa saw nearly 1,900 kamikaze sorties; their attacks sank dozens of U.S. ships. These attacks inflicted heavy losses on the invasion fleet.

Timeline of the Battle

- Late March 1945 – Pre-landing and Kerama Islands: In late March, preliminary landings secured the Kerama Islands off Okinawa’s west coast. Allied forces isolated Okinawa by March 26, then occupied nearby Keise Shima by March 31. These islands provided anchorages and airfields to support the main invasion.

- April 1, 1945 (L-Day) – Amphibious Assault: On April 1, U.S. Marines and soldiers hit the Hagushi beaches on Okinawa’s west coast. The landings were largely unopposed initially, allowing the 96th and 7th Infantry Divisions (Army) and the 1st & 6th Marine Divisions to secure the shoreline and advance inland. By nightfall L-Day, thousands of American troops were ashore (without major casualties) and key positions like Yomitan and Kadena Airfields began to fall.

- Early–Mid April – Northern Sector & Motobu Peninsula: After L-Day, elements of the U.S. 6th Marine Division drove north toward the Motobu Peninsula. By April 9, they assaulted heavily fortified ridges (like Cactus Ridge and Sugar Hill). Over the next week they cleared Motobu, completing the capture of northern Okinawa by about April 18. Concurrently, the U.S. 77th Infantry Division took nearby Ie Shima (April 16–18), where famed war correspondent Ernie Pyle was killed.

- Mid–Late April 1945 – Shuri Line Battles: In mid-April, U.S. forces pivoted south toward Shuri, encountering the Japanese Machinato Line and then the main Shuri Line of pillboxes and bunkers. The Machinato Line (south of Naha) was cracked by late April after heavy fighting. The toughest resistance lay at Kakazu Ridge, Sugar Loaf, Half-Moon and Horseshoe hills protecting Shuri. American assault units (1st and 6th Marines) repeatedly attacked these “Goddamned little hills” under intense artillery and machine-gun fire, suffering heavy casualties in April–May.

- May 1945 – Fall of Shuri: By early May the U.S. Fifth Army closed on Shuri. After brutal frontal assaults, Shuri Castle fell in late May. American and Japanese forces then slugged it out in dense jungle to the south. Torrential rains in May slowed operations, but U.S. forces gradually compressed the defenders toward the island’s southern tip.

- June 22–23, 1945 – End of Resistance (“Irei no Hi”): U.S. XXIV Corps declared Okinawa secure on June 21. On June 22 Lieutenant-General Simon Bolivar Buckner (U.S.) was killed by enemy fire. That afternoon, Japanese Lieutenant-General Mitsuru Ushijima (32nd Army commander) and Rear-Admiral Ota committed ritual suicide, marking the collapse of organized resistance. Okinawa’s intense fighting had lasted 82 days. The next day, June 23 was later designated Irei no Hi – Okinawa’s Memorial Day – to console the souls of the war dead.

- Late June–Early July 1945 – Aftermath: In early July, small pockets of Japanese holdouts surrendered or were cleared. The battle left the landscape devastated – once-greens turned into a “scarred moonscape” of bomb craters and destroyed towns. The U.S. established field hospitals for the enormous number of wounded and began major humanitarian efforts. Okinawan civilians and surviving Japanese soldiers emerged from countless caves (gama) and shelters (80,000 did so by war’s end), many of them injured and traumatized.

Human Cost & Legacy

Monument and Memory: The human toll was staggering. Modern accounts note 110,000 Japanese/conscripts killed and over 100,000 civilians (roughly one-third of Okinawa’s pre-war population). Many Okinawans were caught in the crossfire or persuaded to suicide by wartime propaganda. For example, after landing near Torii Station (south Okinawa), U.S. troops met local civilians in Shimuku Gama cave. Two Okinawan-Americans convinced fearful villagers they would not be harmed – likely saving ~1,000 lives. In contrast, about 84 residents of nearby Chibichiri Gama killed themselves (and their children) with grenades and poison, tragically “foolishly [believing] the enemy to be like the propaganda said”.

By war’s end, somber memorials rose across Okinawa. The Okinawa Peace Memorial Park (Itoman) – designed by Kenzo Tange and opened in 1975 – and its Cornerstone of Peace monument list all who died on Okinawa: Japanese and Allied, civilian and military. Today visitors pause at cenotaphs and laid offerings. On Irei no Hi (June 23), thousands (e.g. 4,000 in 2025) gather in black attire, lighting incense and flowers by the Cornerstone – a powerful symbol of Okinawans’ commitment to forgiveness and peace. This inclusive memorial embodies the “Okinawan Heart” – a post-war ethos of valuing each human life and rejecting war.

Beyond the park, the scars of battle endured. Many cultural sites were destroyed – most famously Shuri Castle (Okinawa’s royal palace), which was shelled and burned in 1945. (Rebuilt in 1992 as a UNESCO heritage site, it stands as a symbol of Okinawan resilience.) Casualties and ruin shaped Okinawan identity for decades. The Himeyuri Peace Museum (Itoman) and other local institutions arose to preserve oral histories and artifacts, teaching new generations about the civilian experience (e.g. the student-nurse corps memorialized by Himeyuri). Remembering Okinawa’s suffering is deeply ingrained today – every June 23 stores close and people attend ceremonies island-wide. As Governor Denny Tamaki said at the 2025 ceremony, they reflect on “the lessons from the battle” and pray for peace, mindful of the heavy civilian burden (over 240,000 names on the memorials).

Planning Your Visit (Respectful & Practical)

Peace Memorial Park & Prefectural Peace Museum (Itoman, Mabuni Hill)

This is the island’s foremost WWII memorial. The Park grounds (open 24/7) feature the Flame of Peace, Peace Hall tower, and serene ocean views. The Prefectural Peace Memorial Museum (open 9:00–17:00; admission ~300¥) provides a thorough battle overview. Its permanent exhibits (5 rooms) cover Ryukyuan history, wartime Okinawa, and harrowing civilian stories. Visitors should allow 2–3 hours here. The museum is wheelchair-accessible, with paved paths through the park, but note the hill terrain. Honor the setting by keeping voices low (it’s a place of contemplation) and dressing respectfully. Photography: Allowed outdoors (monuments, grounds) but please be discreet around mourners. (Inscription rubbings are common; for example, visitors trace names on the Cornerstone for loved ones.)

Peace Memorial Museum: Inside, the Cornerstone of Peace lists 240,000+ names of the fallen. Take time at the cenotaphs and gazing platform overlooking Mabuni Hill. On-site amenities include restrooms and a snack stand. The park has ample parking and is reachable by bus (#89 from Naha to Itoman terminal, then local bus). Peak times: Okinawan Memorial Day (June 23) is very crowded (open-air ceremonies), but seeing a minute of silence at noon can be moving.

Himeyuri Peace Museum (Itoman)

Located 2–3 miles west of the Peace Park, the Himeyuri Museum memorializes ~240 mostly high-school girls who tended wounded soldiers in underground caves. The museum’s six exhibition rooms (arranged around a courtyard) use bilingual text and photos to convey their story. It’s deeply emotional – expect many Japanese visitors to be moved to tears. Plan at least 30 minutes (often 1 hour) to view all exhibits. The Himeyuri Tower and cenotaph (outside the museum) are accessible even when the building is closed. Accessibility: Wheelchair-assisted tours are available and you can rent one on-site. Photography: Forbidden inside exhibition rooms; allowed in lobby/courtyard and outside. The museum has no onsite parking (visitors may park at nearby souvenir shops). It is often included on Naha-Itoman tour buses (though these allow only ~30 min, which many find rushed). To avoid crowds, go early.

Former Japanese Navy Underground Headquarters (Naha/Tomigusuku)

Just south of Naha, this tunnel complex was the Japanese Navy’s command center in 1945. It’s now the Naval Underground HQ Peace Memorial Park. A visitor center (free) contains a small exhibit of artifacts. From there descend 105 steps into 300 meters of original wartime tunnels. You’ll pass the commander’s office, operating rooms and staff quarters preserved as they were, plus powerfully eerie scenes (e.g. walls “riddled with a grenade” from a suicide). Accessibility: The entrance is down many steps, but wheelchair users can enter via the exit ramp on the way out. The site includes an observatory, a Tower of Remembrance to Admiral Ota (who led the Navy troops here and later committed suicide), and walking paths with sea views. Allow about 30–40 minutes to tour the tunnels and exhibits. Buses #33, #46 or #101 from Naha (20 min) stop near the park; the car route (via Meiji Bridge and Route 7) is well-signposted. Photography: Allowed (no special restrictions noted). There are restrooms in the visitor center.

Key Battle Sites

A few accessible sites mark major fights:

- Kakazu Ridge / Urasoe-Yonabaru District: Now “Kakazu Takadai Park,” this northern ridge offered Americans a sweeping view of central Okinawa. It was one of the terraced ridges attacked on April 9, 1945. Fierce Japanese fire from concrete bunkers and pillboxes cut U.S. gains; it took ~15 days and thousands of casualties to secure the ridge. Today you can climb the observation tower (soaring over farm fields) and see wartime relics: a bullet-pocked concrete wall and a fenced-off bunker entrance on the hillsides. (photo: view from Kakazu Ridge looking north)

- Hacksaw Ridge (Maeda Escarpment): Just south of Kakazu, this steep cliff (featured in the film Hacksaw Ridge) was another bloody Marine objective in mid-April 1945. A war memorial stands near the trailhead. (Though famous from Hollywood, much of the original terrain was reconstructed postwar.)

- Sugar Loaf Hill (Conical Hill, Itoman): South Okinawa’s most notorious position, attacked by the U.S. 6th Marine Division in May 1945. Multiple assaults saw heavy carnage. Today it’s a small park with plaques, plus Gun’yoh Tunnel remains. Veterans’ photos on display recall “Goddamned little hill” battles.

- Shuri Castle Ruins (Naha): Once the 32nd Army HQ, Shuri Castle was razed in May 1945. Only the stone walls and foundations remain; the main hall was reconstructed by 1992. (Note: the rebuilt castle buildings were destroyed by fire in 2019 and are under restoration.) In the castle’s basement tunnels (partially reopened as of 2025) you can glimpse where Okinawan command staff sheltered.

These sites mostly have no admission fee. Terrain can be uneven (short hikes, stairs at Kakazu and Hacksaw), so wear sturdy shoes. Interpretive signs are in Japanese only, so a guide or prior reading can help. Visiting these sites can add context between museum stops.

Route Ideas

To see it all without stress, split your time:

- Half-day Itoman loop: From Naha, take bus or drive 30–45 min south to Peace Memorial Park. Spend ~2–3h there (museum + monuments). Then walk or short bus north to Himeyuri (~15 min), and allow ~1h for the museum and tower.

- Half-day Naha loop: Focus on central Okinawa – start at the Former Navy Headquarters (30–45 min), then explore Naha’s war history (Okinawa Prefectural Museum has WWII exhibits) or Shuri Castle (allow 1–2h).

- Combined full day: Morning in Itoman, afternoon in Naha (or vice versa). Driving from Itoman back to Naha takes ~45 min. Independent travel is flexible; note that organized tour buses often give only ~30 min at each stop, which can feel rushed.

Etiquette & Sensitivity

These are solemn sites. Always speak quietly and move respectfully. At the Peace Park and Himeyuri, as the museum advises, maintain a subdued demeanor. Dress modestly (e.g. shoulders covered, no beachwear or loud colors) out of respect. Observe any house rules: Himeyuri forbids photography inside the exhibition rooms (photos are only allowed in lobbies and outdoors). Be patient and defer to school groups or local elders when visiting — many Okinawan students visit these sites regularly. When in doubt, follow the lead of Japanese visitors: bow at monuments, refrain from loud conversations, and take only memories (no souvenirs from the sites themselves). If visiting on June 23 (Irei no Hi), you may encounter a formal ceremony – stand quietly at the edges to observe.

Accessibility & Tips

Most war memorials have improved access but can involve hills or stairs. Wheelchairs: The Peace Park grounds and museum are wheelchair-accessible (paths are paved, though hilly). Himeyuri provides assisted-wheelchair tours (three wheelchairs are available to rent). At the Navy Headquarters, the entrance is down 105 steps but there is a gentle ramp to exit (so a wheelchair can enter via the exit path). Strollers: The Peace Park paths and Himeyuri courtyard are stroller-friendly, but the Navy HQ stairs make it unsuitable for small children there. Climate: Okinawa is tropical. Sunscreen, hats and water are a must in summer. Rain covers or umbrellas are also essential: the rainy season runs roughly mid-May to late June, and typhoons can occur June–September. Summer visits mean high heat and humidity, so plan breaks in air-conditioned museum spaces. Parking is ample at Peace Park (free) and Navy HQ; Himeyuri relies on nearby lots (no official lot). Restrooms are available at the museums and park. Snack shops or vending machines are in or near the visitor centers. Finally, even if you’re a lay traveler, try to prepare by reading a little about Okinawa’s history: it will deepen your appreciation and help you engage respectfully (see “How to Learn More” below).

Best Times to Go

Okinawa has long summers (often >30°C) and a rainy season (mid-May–June). The spring months (Apr–May) and autumn (Oct–Nov) have milder weather and fewer storms. June 23: If you visit on Irei no Hi, expect special events. It can pour rain (typhoon season) or be very humid, but you’ll witness meaningful memorial ceremonies. If crowds and weather are concerns, visiting outside mid-May to mid-July avoids the worst heat and typhoon risk. Crowds generally peak on public holidays, whereas weekdays in April–May or September see fewer tourists, making for a quieter experience.

How to Learn More

For deeper understanding, consult a mix of primary sources, museums, and scholarly works. Start with official museum resources: the Okinawa Prefectural Peace Memorial Museum has publications and exhibits grounded in oral histories, and the Himeyuri Museum’s guidebook (available in English) includes survivor testimonies. The U.S. Army’s Okinawa: The Last Battle (Appleman et al.) and academic histories detail campaign phases with maps and stats. Eyewitness accounts – for example, videotaped veteran testimonies or survivor memoirs – bring personal context. Online, reputable sites (e.g. the Naval History and Heritage Command, Pacific War Museum, and Okinawa Prefecture archives) provide photos and documents. Always cross-check figures and names: sources vary (for instance, some list ~142,000 civilian casualties versus ~94,000), so compare multiple accounts. In general, rely on history-centered publications (not blogs) and consider both American and Okinawan perspectives for balance. Many museum shops sell English books and DVDs on Okinawa’s wartime story, which can also be useful. If you visit in person, free “peace guide” volunteers often give tours at these sites – they can answer questions and share local insights.

Glossary

- Operation Iceberg: Allied codename for the 1945 Okinawa campaign.

- Shuri Line: Japan’s fortified defense around Shuri Castle in southern Okinawa.

- Gama (がま): Okinawan term for caves used as wartime shelters.

- Irei no Hi (慰霊の日): Okinawa’s Memorial Day on June 23, marking the battle’s end.

- Kamikaze: Japanese suicide attack aircraft (“divine wind”); over 1,900 sorties flew in Okinawa, sinking dozens of ships.

Traveler FAQ

When did the Battle of Okinawa start and end? The invasion began April 1, 1945 (L-Day) and fighting continued through spring. The U.S. 10th Army declared Okinawa secured on June 21, and Japanese resistance formally ended June 22, 1945. Okinawa now observes June 23 as Memorial Day.

Why was Okinawa strategically important in 1945? Okinawa lies close to Japan’s main islands. Capturing it provided airfields and harbors for an invasion of Japan. Military historians note Operation Iceberg was the Pacific War’s largest landing, crucial for shortening supply lines to Japan.

How many civilians and soldiers died? Estimated U.S. deaths were ~12,520. Japanese military losses (including conscripted Okinawans) were ~110,000. Civilian deaths were enormous – around 100,000 Okinawan civilians (some estimates ~142,000 total) perished. In total over 240,000 names are now inscribed on Okinawa’s memorials.

What is Irei no Hi and how is it observed? Irei no Hi (慰霊の日) is Okinawa’s Memorial Day, held June 23 each year. It commemorates the 1945 end of battle. On this day, large ceremonies occur at Peace Memorial Park (with government officials and families). Thousands dress in black, offering incense and flowers to the war dead. There’s a moment of silence at noon throughout the island.

Which museum should I visit first if I have limited time? We recommend the Prefectural Peace Memorial Museum in Itoman first. It covers the entire Battle of Okinawa – from historical background to civilian impact – in multiple rooms. It provides essential context. Himeyuri’s museum, while moving, focuses on a specific group (student nurses), so it’s better as a second stop if time allows.

Is the Former Navy Underground HQ suitable for children? Somewhat – but use caution. The tunnels are preserved in a dark, confined state. Children who are uncomfortable in tight spaces or unfamiliar with war history may find it scary. The underground tour takes only 30–40 minutes. The above-ground museum room is simple and easier for kids. If you do go, supervise young ones on the stairs (105 steps) and explain what they’ll see.

Can I take photos at museums and memorials? Generally yes, except where noted. Himeyuri Museum strictly prohibits photography in its exhibit rooms – you may only take pictures in the lobby or outdoors. Peace Park and Museum: Photos are welcome on the grounds and in most displays; just be mindful of mourners and avoid flash near sensitive artifacts. Navy HQ: Visitors often photograph in the tunnels and museum freely. Always obey posted signs and never use drones or tripods in these solemn areas.

Are the exhibits available in English/Japanese/Chinese? Yes. Exhibit texts at the Himeyuri and Peace Memorial museums are in Japanese and English. The Peace Memorial Museum also has exhibit captions in English (and some Chinese). The Navy Headquarters provides multilingual pamphlets (English, Chinese, Korean) and its small museum has English captions. Audio guides (in English) can often be rented. In short, all core exhibits have English descriptions.

How should I allocate time between Peace Memorial Park and Himeyuri? A good rule is 2–3 hours at Peace Memorial Park (museum + outdoor monuments) and about 1 hour at Himeyuri (enough to read most panels). If doing both in one day, an example schedule is: morning at Peace Park (2–3h, including museum and Cornerstone), lunch in Itoman, then afternoon 1h at Himeyuri. The sites are about 5 km apart. Note that tour groups often rush these stops; self-planning lets you take the time you need.

What should I wear/bring for outdoor memorial sites? Wear comfortable walking shoes and light, modest clothing (e.g. cover shoulders) out of respect. Okinawa is hot and sunny – bring sunscreen, a hat and plenty of water. An umbrella or raincoat is wise, especially June–September (rainy/typhoon season). You may bring flowers or incense for the monuments (the park sells incense). Avoid flash photography near memorials. Modesty (no beachwear or revealing clothing) is appreciated even outdoors.

Are these sites accessible for wheelchairs or strollers? Yes, with some limitations. The Peace Park grounds and museum are wheelchair- and stroller-friendly (paved paths, ramps). Himeyuri Museum allows wheelchair access; assisted wheelchairs can be rented. Former Navy HQ: has 105 steps at the entrance, but it is accessible via the exit ramp (so a wheelchair user can enter through that way). Strollers can go in most areas except the Navy tunnels (stairs). All sites have accessible restrooms. Check each site’s info if you have specific mobility concerns.

How can I engage respectfully if I’m unfamiliar with the history? First, a little prep helps – read a concise overview of the battle before your trip. On-site, follow the local cues: speak softly, follow posted guidelines, and treat exhibits solemnly. Listen quietly if others are reading testimony excerpts (as at Himeyuri). Feel free to ask museum staff courteous questions. Show empathy: for example, if you see Okinawan elder survivors at a memorial, allow them personal space. Embrace the learning opportunity while remembering this is a tragic story first and foremost; avoid any behavior that might be seen as trivializing the loss (e.g. loud laughing or joking on the grounds). Remember that respectful attention and courtesy are the best forms of engagement.

Visit Okinawa’s wartime sites with care and context

Markets, WWII tunnels and southern coastline:

Ask us about adding extra museum time to a custom private tour: